Your cart is currently empty!

Tag: writing

-

Death and it’s Brilliant Life in Fiction

For as long as people have told stories, they’ve used death to show the finality of characters’ lives and their own fears of mortality in the audience. Death serves many purposes within fiction, but its exact nature can vary widely depending on the point of view of the author and the context in which it occurs. No matter how you choose to use death in your fiction, however, there are some universal truths that every writer should know before tackling this powerful topic.

Death as Motivation

In fiction, death is often a character’s motivation. There are countless stories where someone lost their life, and now their family wants to avenge them. Although it may seem like we use death as a blunt tool to move a plot forward, it can have much more significance. In John Steinbeck’s East of Eden, Cathy Ames sees her own experience mirrored by that of her dead mother and becomes an entirely different person who finally has some semblance of what it means to be alive.

Similarly, Hamlet spends most of his story trying to exact revenge for his father, King Hamlet—and although he accomplishes that task at last through bloody murder, Hamlet gains far more from learning who he really is than from gaining a pound of flesh. It seems obvious at first glance: characters use death as fuel for action and passion in narratives all over literature. But there’s so much nuance here beyond just oh I see why you would use your parent’s or child’s death to push your character into doing something! Well done you! Instead, these tragedies—or accidental deaths or murders—can deepen our understanding of characters both within a story and outside one.

Death as Ritual

There’s something inherently fascinating about death, especially with fictional characters. Why is it a character’s death can completely enrage us, yet also moved to tears? Why is it we find value in certain character deaths and not others? We aren’t reading about real people—we can accept (for example) a murder victim as an unfortunate part of a detective novel without having our own feelings towards homicide affected. So, what makes one character’s death stick with us more than another?

The answer may lie in ritual. Whether characters are aware of their impending doom or ignorant until it’s too late (think The Sixth Sense), most fictional deaths follow a somewhat formulaic structure. What does ritual do for us? To put it simply, a pattern like death creates order where there might otherwise be chaos. By following specific steps each time we go through a process (like dying), we know how things will play out before they happen—and afterwards. This predictability comforts us; if things don’t go according to plan… well, plans rarely go off exactly as intended, anyway.

Ritual also promotes progression: knowing that things will probably turn out well after death means that you have nothing to lose by being aggressive; you’ll still end up at your ultimate destination regardless of how hard you push yourself on route there.

Finally, ritual helps us cope. Not only do we need some sort of closure regarding our lives, but seeing other characters deal with death allows us to feel okay about it ourselves—after all, someone else went through it successfully, so perhaps we’ll make it out alive as well. I’ll link these two points using Dracula, which follows both dramatic death scenes and classic vampire folklore to create an atmosphere in which any random character has a chance of getting picked off next… while forcing several other characters into unnatural sleep during daytime hours before setting them free again at nightfall. For someone who’s terrified by vampires, surviving Dracula must feel akin to living inside her own personal Hollywood horror movie!

Death as Catalyst

In both film and literature, we often use death as a catalyst for significant change. Some stories hinge on its use as a plot device—the inciting incident that gets everything going. Others use it to illustrate how even life’s most terrible moments can be valuable for their ability to bring people together. For example, The Fault in Our Stars uses death to give Hazel and Gus’ relationship new meaning and drive.

While death is an unavoidable part of life, fiction gives us the opportunity to reflect on what it means and how we live our lives by showing us how others handle theirs—especially when they’ve lived short ones. Understanding that helps us find value in ourselves as well. No matter what your interests or goals are, no matter where you are in your career or your day-to-day life, there is value to be found somewhere. Whether you’re living out your dreams or daydreaming about doing so, you always have something special to add—even if it doesn’t seem like it sometimes.

Looking at death through fiction gives us insight into genuine life, love, and loss. This can help us learn not only why others should appreciate us but also how we should appreciate them as well; even more important than that, though, it shows us why we should appreciate ourselves.

Death as Plot Device

A common occurrence in fiction is death as a plot device. It doesn’t matter if it’s a main character or minor character, everyone dies. If you are considering killing someone off, think about whether that death has any real meaning to your story. If it does, great! Write on. However, if it seems like a hollow addition to your story and there’s no other reason for their death to occur besides adding some excitement, then consider replacing that with something else that is more purposeful to your story (another conflict? A betrayal? Someone lying unconscious on the ground?).

The removal of one detail may add to your overall story by allowing another to take its place. If they die—who gets their stuff? Often when characters die, a lot of authors will just jump into what new things they can gain from those characters passing. Do you do that? Consider instead changing things so those objects don’t exist anymore (or at least change what they can do). This allows room for another set of elements in your world, which helps change how we view reality and challenge expectations throughout a book. Just because people love The Lord of the Rings, doesn’t mean we should all be writing books with spellbound doors; but books where magical items have changed based on previous experience might really bring magic back into our worlds!

Death as Message

Readers will often interpret characters’ deaths as a message or lesson. In these cases, death is used to emphasize how precarious life is. This practice is most common among characters who the writer hopes will elicit emotional responses from readers. For example, we often use death to get readers to empathize with a protagonist or champion their cause. Other times, authors use tragic deaths to impart wisdom (e.g., what not to do) or teach important lessons (e.g., those who don’t learn from history are doomed to repeat it). If your goal is to convey something significant through character death, make sure you choose your victims wisely—or you might end up with a message that no one likes!

Death as Tragedy

One of our greatest fears is death; we hope it never happens. When it does, we grieve. But even though death is inevitable, rarely do fiction writers truly allow their characters to come to terms with what that means. In real life, grieving and mourning are a slow process as we accept that our loved one won’t be around anymore. But in fiction, someone usually dies suddenly or violently and then they’re gone—the end. Perhaps some grief will linger on, but otherwise, there’s no working through it. When a character dies unexpectedly or violently at the hands of another character or from an outside force like disease or natural disaster, it could (and often does) make for great drama.

Tragedy is drama. A tragedy involves an individual and all those around them, led to self-destruction by a tragic flaw or fatal character flaw. In Shakespeare’s tragedies (the most famous being Hamlet), death often comes at a critical turning point, especially when an individual cannot act on crucial information. For example, in Shakespeare’s play Julius Caesar, Mark Antony is murdered during his funeral.

This leads to more chaos among Caesar’s political supporters, who cannot understand that Brutus has killed Antony not because he thinks Caesar shouldn’t be honored, but because he wants revenge for Caesar’s death. The result of Brutus’ actions is destruction as civil war breaks out shortly after Caesar’s murder. Because no one could stop their vengeful behavior, they suffer before Rome finally emerges under Augustus Caesar (who turns out to have been part of Marcus Antonius’ plot all along).

Death as Mystery

There’s something morbidly exciting about murder mysteries. Even if you don’t know who killed poor Mr. Boddy, there’s a certain thrill to solving even an imaginary crime. This isn’t entirely surprising: although we might not like to admit it, death is terrifying. When it happens at our own hands (either actively or passively), and when we do not know how or why it happened, it can feel almost suffocating. We want answers; understanding gives us power over both death and fear. The death of a fictional character offers all these things and more—and that’s why so many readers get hooked on murder mysteries!

One of my favorite things about reading mysteries is that they often lead to some serious contemplation. There’s something enticing about death—the fact that it’s so out of our control is fascinating to me, and what better way to think about mortality than through a good mystery? When you have time, try watching Sherlock (another substantial source for death-related contemplation) or pick up any thriller by Gillian Flynn—you won’t regret it. If all else fails, at least you’ll get an entertaining story!

Death From Behind the Scenes

In real life, we don’t know when death will come, and that has always been true. But now, more than ever before, we can imagine a world without death—thanks to medicine and technology. What does it mean for storytelling if characters can’t die? Will death remain an important part of narrative? If not, what purpose does it serve?

In literature, death is a versatile character. As humans try to make sense of death, they look at life’s most popular stories. Themes involving death are prevalent throughout fiction; after all, when was the last time you read a story without at least one death? What’s more interesting is how writers use death as an active agent rather than just an element of storytelling. Whether it’s exposing characters’ motivations or tricking readers into turning pages faster—death is used strategically and often memorably.

We’re entering a world where our lack of understanding regarding death will become increasingly unrealistic. But even if science catches up and surpasses our imagination, we’ll always need stories to explore themes like love, greed, hate, ambition—and yes… even death. So perhaps our best bet is to embrace uncertainty by seeking innovative ways for authors and artists to integrate mortality into fictional worlds.

We’ll always be curious about death—no matter how it’s presented—because it promises change and fulfillment from deep within ourselves. Fictional deaths will never replace real ones—but maybe we should let both remind us that nothing lasts forever.

-R.E.

-

Self Care is Important for Writers

Writing can be incredibly rewarding, but it’s not simple work! A lot of writers end up dealing with a lot of stress and emotional instability in their personal lives and their writing lives. It’s important to take care of yourself, both physically and mentally, if you want to remain healthy and able to continue writing for the long haul! Self Care is as important to a writer as the desk they work from. Learn why and read about some helpful resources for maintaining your mental health.Here are some ways to keep yourself sane as a writer so that you can avoid burnout, anxiety, or other emotional problems related to your writing career.

Develop Good Habits

This should come as no surprise, but good habits make all of us feel better. And we already know that writers have enough to worry about—no need for you to worry about your health, too. Write at least three healthy habits and give yourself a week or two (depending on how bad things are) to incorporate them into your life.

Remember: if you don’t take care of yourself, you can’t do your best work. Setting up small, daily goals is one of many ways to improve your self-care habits. Here are some ideas: drink more water; walk around while you talk on the phone; meditate after breakfast. Make these changes one at a time, so they don’t seem like much extra work and before long, they will be part of who you are!

Eat Better

Give your body what it needs for optimum energy with healthy, nutrient-rich foods. Simple carbs and processed foods can leave you feeling lethargic and sluggish, making it hard to get into a creative groove. Eat plenty of vegetables and lean protein so you have plenty of energy for writing, taking care of yourself, or just playing with your kids. It also helps to eat mindfully. For every meal, make sure you’re not distracted by work or other obligations. Finally, slow down. Eating fast can lead to unhealthy weight gain over time due to increased calorie consumption.

Everything in Moderation

Don’t be afraid to indulge now and then; sometimes that chocolate chip cookie really hits the spot. Just make sure you monitor your portions and stay within a reasonable limit most of the time. And if all else fails? Move! Physical activity is absolutely necessary for brain health besides keeping excess pounds at bay. Keep in mind that food is fuel—your body will run best when it has quality fuel (both in terms of quantity and quality). It’s important to take good care of yourself even if you don’t feel like doing much else! You want all your energy focused on writing!

Do whatever helps you achieve optimal productivity without compromising your health too much–and see a doctor if something gets worse instead of better! Besides aiding your health, seeing a doctor could prevent serious future problems from developing.

Exercise

It’s no secret that regular exercise is good for you, but how much exercise do you need? If you want to write regularly and consistently, it’s best if you try to get at least 30 minutes of moderate-intensity exercise (or 20 minutes of intense-intensity exercise) every day. The key with exercising is variety—do lots of different things! And don’t forget about strength training: You need it too.

Staying physically fit will also improve your posture. That can help prevent or ease back pain when typing for long periods of time. Workout routines should include exercises for your legs, abdomen, lower back and upper body; consider doing stretches before each workout.

Breathing exercises are also beneficial. They help reduce stress and strengthen respiratory muscles by filling lungs with more oxygen than normal breathing allows. Regular exercise helps combat disease and makes recovery easier after an illness has set in. Also helps relieve stress, which directly relates to anxiety and depression. These are among many issues writers face frequently during their career. Exercise releases endorphins which make us feel happy; they become naturally triggered by vigorous movement such as fast running or even jumping up and down while playing sports like tennis or soccer.

Have a Routine

When you’re writing every day, it’s important to have some sort of routine. Some writers enjoy working during specific hours of the day. Many need absolute silence, while others prefer lots of background noise. Maybe you work better outside or perhaps sitting in your pajamas works best for you. There are no hard and fast rules—maybe one day it takes five minutes and another day it takes ten hours. If you don’t stick with a routine that works for you, things will probably go haywire. That said, there’s no reason routines shouldn’t change over time—there’s nothing wrong with trying something new! Just evaluate whether something works before going all-in on it.

Build in Writing Breaks

Every day, take some time to do something unrelated to writing that you enjoy. For many people, it’s walking or stretching after sitting still for hours on end. If those things don’t appeal to you, play a quick game of pool or go work out at your local gym. It may surprise you how little time it takes before you feel rejuvenated enough to keep working on your project with new enthusiasm. One essential aspect of surviving as a writer is balancing non-writing activities with your work life. Planning daily writing sessions can lead to writer’s block and burnout.

Instead, schedule your writing breaks into each day and make sure they actually happen. Spend five minutes of every hour doing something unrelated to writing (besides eating or drinking). Give yourself space from your work and you’ll increase your focus when it’s time for focused work. If you find yourself tempted to do non-writing activities during these breaks—go ahead! Walk around and stretch. Get some water. Breathe in nature. Just be sure not to get lost on YouTube or Twitter. For many writers, limiting screen time helps reduce distractions while they’re trying to get words down on paper.

Keep a Journal

Keeping a journal is also an excellent way to get through that writer’s block. The very act of putting thoughts on paper will often spark ideas for story ideas, characters, and plot twists—plus it keeps you practicing your writing skills. By switching off between working on projects and keeping a journal, you can keep yourself sane while still accomplishing work. You might even surprise yourself with some unexpected insights that come during journaling.

There will be periods when you need to sit still and think, such as during an airplane flight. Take advantage of them by journaling about how your story is going so far and what could happen next. The more you write when you don’t need to, even if it’s just one page per week, will help keep ideas flowing and stop the creative block from taking hold!

Don’t Compare Yourself

It’s easy to compare yourself to others who seem more successful. But what seems like failing is often just part of an upward trajectory. A writer who has only published one book isn’t less successful than a writer with multiple books under her belt; she’s simply behind on her career path, and there’s no shame in that. If you feel defeated by someone else’s success, stop and remember that you are where you need to be right now. All of your experiences (even those without obvious value) will bring you where you need to go in due time.

It’s easy to get sucked into comparing yourself to other writers. You see someone with a book deal or six-figure advance and want to know how you could get there—but making comparisons just makes things worse. Don’t compare your rough draft to other people’s finished novels; instead, focus on how far you’ve come. And always remember that everyone has their own journey—and every person’s path is different! Don’t compare yours to anyone else’s. Instead, focus on personal growth over time and celebrate your successes along the way. Remember: Imitation doesn’t make for better writing; it only reinforces bad habits that will keep you from ever becoming successful!

Join a Writers Group

Whether you’re just starting out or have been in it for years, writing can be one of the most isolating professions. People don’t always understand what you do—and why you love it so much—and that can make dealing with rejection and criticism especially hard. But support networks can come in many forms, and some writers find that regular meet-ups with other writers are an essential part of keeping themselves sane.

There are several ways to find or start a group that meets up locally. You might also consider joining your local branch of The Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators (SCBWI) where there are groups dedicated to different writing, such as young adult fiction, middle grade fiction or picture books. While these groups don’t focus on critiquing each others’ work (though they certainly will if desired), they provide mutual support and encouragement.

Writers groups offer members opportunities to network through sharing contacts, events and social media. Other communities like Mastodon’s WritersCoffeeClub also offer online communities in which people share ideas and critique works online rather than face-to-face. And for those who prefer more tactile interactions, workshops run by publishers often offer lots of useful advice from published authors about how to stay motivated, write more consistently and engage readers from a wide range of genres.

De-clutter Your Workspace and Mindset

Clutter can stress us out, take up our attention, and force us to postpone things in order to make way for something else. De-cluttering your physical environment and your mind will help you find peace of mind and get more done—especially if you’re prone to procrastination. The first step is knowing where to start: use some sort of productivity app or plain old pen and paper to break down your projects into manageable chunks.

Get started by letting go of what doesn’t matter right now, mentally (and physically) decluttering whatever space that project takes up in your life/minds, then setting realistic goals for each small task along with deadlines to keep yourself on track. Procrastinators are often perfectionists; focus instead on getting stuff done rather than being perfect at it. Prioritize tasks by writing them down, putting them into lists or with colors/labels/etc., so that you can quickly see what needs doing next (as opposed to having an anxiety attack about it). Similarly, keeping yourself organized helps manage stress and feel accomplished!

Prioritize Health

The benefits of self-care are many, but there’s one in particular that appeals to me: it can positively impact my creative output. If I’m feeling mentally and physically healthy, I’ll be able to produce higher quality content consistently. When we release stress, we have more space for creativity. It is worth it for me—and you—to devote time and energy to caring for ourselves each day.

-R.E.

-

How To Know If You’re A Plotter Or A Pantser

Plotters and pantsers are two very different types of writers, and they approach the writing process in very different ways. Plotters like to have every detail planned out before they start writing, while pantsers prefer to dive right into their stories without any sort of outline or planning.

Plotters vs pantsers is a debate that’s been around almost as long as writing has existed. Is your style more pantser than plotter? Or vice versa? Or is it somewhere in between? Wherever you fall on that spectrum, there’s no denying: A little planning goes a long way towards helping you craft a work you can be proud of—and one that readers will love to read. But which approach works best? The answer depends on your personality and your creative process, but we’ll give you some insight into each approach to help you decide which one is right for you.

Plotters

Plotters outline every detail of their story before they begin writing. They are never surprised by where their story takes them and can usually describe exactly how a book will end from day one. Plotters may use elaborate spreadsheets, detailed character information, and chapter outlines for each book in a series. When plotting out a project, plotters think about questions like: What is my overall goal for each book? What needs to happen first? What details need to be worked out right now? How can I anticipate possible story concerns down the road? How can I plan ahead to address these issues effectively? Where do things get really hairy later on?

Plotters may not have all of these answers at once, but as they write their books and get feedback from editors, beta readers, and critique partners (to name a few), plot holes or inconsistencies become obvious. Plotting doesn’t work for everyone—some people love it while others hate it—but those who don’t mind it enjoy more success getting published and earning higher advances than those who try to figure everything out as they go along.

The Plot Thickens

Plotters tend to write stories that feel more complete because there’s little unexpected left-turns in any given chapter or scene. This is important when pitching ideas and if you’re trying to win over an editor. If you know your characters inside and out, you’ll also be able to play with possibilities within your world much more easily. Plotters typically take longer to publish because they’re doing a lot of extra thinking before getting started on actual writing time. Their process feels slower, but what matters most is consistency and deadlines met. These writers also worry less during edits because they’ve already done so much prep-work. There’s less guesswork involved.

The downside of plotting is that many writers find outlining too restrictive, dull, and unimaginative; some authors even dislike being hemmed in by rigid plans for their characters’ actions instead of letting those choices evolve organically based on what makes sense under certain circumstances and how their characters would actually behave. The best way to know if plotting works for you is to try it! Create an outline—either mental or physical—and see if you find yourself looking forward to turning your big idea into pages upon pages of unforgettable prose.

If you don’t see much joy in planning your novel before you write it, then perhaps you’re better off following another path when it comes time to actually draft your story . . . so let’s talk pantsers!

Pantsers

The Pantsers are people who write without any preconceived idea about how their book will turn out. They start writing and let the story unfold as they go along. In some ways, writing a book is like solving a mystery, you don’t know what’s going to happen until you do it. The first thing they do is sit down and start writing!

Sometimes an outline can help, but more often than not that can be restricting for these writers. Whatever comes next has to flow from what has been written so far. Letting something happen naturally is sometimes difficult for an editor who likes things planned out beforehand! Many pantsers feel that pantsing gives them a ‘naturally flowing’ piece that feels much more authentic than something done by someone who plans everything beforehand.

By The Seat of Your Pants

Writers need to have faith in themselves and trust in their own abilities, allowing those inner voices (inner muse?) lead the way. Otherwise, where would we all be with reading such interesting books? We wouldn’t have come across such great tales if writers hadn’t taken risks on their stories and letting them grow organically into compelling plots!

Pantsers can run on instinct and come up with characters, motivations, and events as they go along. These writers follow wherever inspiration takes them through each word, yet con’s include rushing through storylines and coming up with issues later in progression due to lack of planning properly at first. The pantsing method allows for great flexibility; however, that comes at a cost. Consistency within your plot may be difficult to achieve if you write by seat of your pants.

It also takes quite a bit longer for first drafts since you’re constantly revising your material until it feels right. When readers find flaws in your story (i.e., major plot holes), it might be more difficult than usual to fix said problems because you won’t have a detailed outline upon which you can rely.

No Wrong Way to Write

There’s no wrong answer. Many writers even prefer moving between the two in their process. My method, for instance, starts with pantsing in a simplified program – one that eliminates distractions. I work through about thirty percent of the story, letting it form organically.

In that stage, the story is a ball of wet clay, and I am rolling it around in my hands, feeling it, letting it take strange shapes. Eventually the clay begins to resemble something recognizable and that’s when I move it into a structure-based program.

Here is where the plotting starts in earnest. Where previously, I had been noting potential patterns, now I am pairing them as two ends of a curve. Using narrative tools like character arcs, crisis points, turning points, core questions and themes to pair with those curves.

I try to come up with 3-5 pairs at any given time. It might be: someone’s secret comes out; they reach an all-time low; but then has a breakthrough moment as someone important opens up their heart to them again; everyone (including themselves) sees real growth from that point on… Another pair might be: Someone wants something (rescue); They do everything possible to obtain it (chase); But it never appears no matter how much they chase after it.

Do What Feels Right

By using both methods I allow the story to develop organically. If, at some point later in the plotting, I decide to deviate I am comfortable doing so knowing that I will return to form once the idea has been given room to grow, to breathe. Instead of working with a single outline, trying to force every idea into place before writing a word—an approach I find leads inevitably to writer’s block—I prefer a tool that allows me to take on board new ideas and let them evolve as my book does.

That’s what works for me and my own process for creating stories; it may not work for everyone else but why not give it a try? Figure out what works best for you! It doesn’t matter if you are just starting out as an author or an experienced writer: we all have different ways of approaching our craft and these are two proven approaches. Try them out and see how they suit your style. Take a look at our list of 10 Great Books We Love About Writing for more inspiration on finding your writing style.

We’ve all heard it said that every writer is a little bit of both. That adage couldn’t be truer. Each and every one of us has our own unique style and process for creating stories. There is no right way to write a book. So, if you haven’t already, I encourage you to try both plotting and pantsing out loud with friends, family members, colleagues – whoever will listen! Find out what works best for you then run with it. Your favorite author may swear by pantsing, but that doesn’t mean you have to follow in their footsteps.

Don’t Be Afraid to Change

Most writers start out as one type and become another, often within a matter of months. Be open-minded and willing to experiment, regardless of which writing style you choose. Whether you’re a planner or a seer, remember that once you have written your first draft, there’s no such thing as too much planning. (But don’t plan so much that you stop writing!) It takes time to figure out what works best for you, but in order to do that, you need practice.

Regardless of what type of writer you are now or hope to be later on, write! The more you write and learn about yourself as a writer and reader—and how they go together—the better off everyone will be. And if neither method is working for you right now, try practicing both! (See what I did there?) As we all know: Practice makes perfect. So get busy…writing!

-R.E.

-

How Research Empowers Your Writing

Coffee Talk:

When you are writing fiction, thorough research can add realism to your narrative, heighten the sense of mystery in your story, and even help you to avoid clichés in your work. However, it’s important to remember that too much research can also get in the way of your storytelling and make it difficult for your readers to immerse themselves in the world you created. Use this guide on the power of research in writing fiction to learn how to get the most out of your research without wasting too much time getting bogged down in details you don’t need.

Research Can Save Your Story

An aspiring author might ask How can I incorporate research into my fiction? As part of their creative process, authors are faced with determining where information on a subject will be found. The general rule is that an author’s imagination is his primary research tool, but it’s also important to note that proper research can add realism to a narrative. Care should be taken, however, to avoid over researching and subsequently over describing when you are trying to relay the information on a subject. As writer Stephen King said,

‘The story begins in the Writer’s imagination but ends in the readers.’

The very best way to flesh out your story is by using your own vivid language so that you can paint a detailed picture for your reader’s mind. Always keep in mind why you are telling your story. Readers don’t want pages upon pages of descriptive paragraphs about how an object looks or feels. Instead they want you to get straight into narrating what happens next without stopping for dialogue or description. Why were they on vacation? Where did they go? Who was with them? Why did they suddenly snap at their husband or wife when he mentioned how hungry he was while they were driving to dinner? It all matters because every detail of every sentence adds character development and more depth to your narrative.

That depth must be properly managed with believable volume.

As we know, less is more and something as small as over-describing a room or a house can spoil an entire story if not handled appropriately. Equally, omitting details that add texture to characters and settings can leave the story feeling hollow. The proper research can literally save your story. If you are creating a character’s vehicle, you need to learn exactly how that vehicle operates. What are its features? What does it do when you push that button? How does it work when you turn on that knob? These kinds of questions will also lead you down avenues where you discover new ways for your character to interact with his car even in stressful situations which could lead to exceptional writing opportunities for these characters. As well writing styles evolve constantly so do rules for language use, better nuances added in descriptions enrich stories while time spent doing things well adds authenticity people crave from fiction they read today.

Why is Research Important?

When you write fiction, you want to give your readers as much authenticity as possible. To do that, you must do your research. Reading about how something is done and why it’s done a certain way will help you understand how to write about those activities and processes. For example, let’s say that one of your characters is a lawyer. Your character goes into court and presents his case. If you don’t know anything about what a lawyer does, it’ll be difficult for you to describe the courtroom scene accurately. But if you take time to learn about courtroom protocol and presentation tactics, then writing such a scene becomes easier because there won’t be any gaps or inaccuracies in your description. Through doing your own research, then honing that information into a story, you can create novels that are more authentic and realistic for readers—and achieve great success with them! Storytelling has been around since humans began telling tales around firesides.

What Does Research Entail?

Researching a story entails finding material to draw from. This may include government documents, records, interviews with real people or even simply referencing books or articles on similar topics. Once you have collected your information, organize it into relevant points that will be most useful to you as an author. Too much research can detract from your ability to tell a story quickly and accurately. Be aware of over-researching by outlining what you know about your subject matter before beginning research so that you don’t waste time gathering material that isn’t pertinent to your book’s plotline. The most important thing is choosing facts wisely; don’t overwhelm readers with unnecessary facts and figures, but make sure they know exactly what they need to know about their character or setting at any given moment during the narrative.

When I’m writing about a specific model of boat, I learn as much as possible about that boat. The dimensions, the history – both manufacturing and sales – the reputation, the main competitors. I want to know what famous person loved it and who hated it. I need to know what color it never came in and what nickname it got from professional boat racers when it was introduced. When I’m writing about the boat, I need to know all of this to inform my image of the boat. The reader, however, just needs to know enough about the boat to inform the story.

Tips For Using Research Wisely

Good writers know when they’ve gotten as much as they can out of research and it’s time to start writing. A story is not a resource. It is something that must be carefully distilled, and if you’re focusing too much on your resources, you’re going to end up with a data dump rather than a story. The goal isn’t to cram in all available information about how something works or looks or behaves; instead, you need to find what’s essential and eliminate what isn’t. Carefully select your sources, use them well and wisely—and let them serve your story!

The nuances that you uncover while researching are just as important as the more obvious facts.

Do you have a sense of just how much detail you’re putting into your story? Are you spending more time describing settings and actions than advancing your plot? Are there sections where nothing much is happening, but you feel like you need to explain things instead of trusting your readers to infer for themselves? Is your character’s speech stiffer than it needs to be because you’ve found an online slang dictionary? If so, back up and take another look at what you’re doing. Just because it’s on Wikipedia doesn’t mean it belongs in your book.Too Much of a Good Thing

Over-researching your story can be as much a problem as not researching enough. If you’re enjoying yourself too much digging up interesting tidbits, you can easily lose sight of your story’s ultimate purpose—telling an entertaining tale. Too many details will weigh down your prose and distract readers from what is actually happening. Use research to improve your writing, but don’t let it take over completely. Once you’ve collected all your information, close out those extra tabs; they won’t help you when your editor starts asking pointed questions about why each character speaks with a British accent. The key to weaving together fact and fiction is knowing when to stop researching so that you’re left with just enough detail for realism without overdoing it or exhausting yourself. That said, if something doesn’t sound right or makes no sense, don’t ignore it! Go back through everything again until everything aligns perfectly with each other.

When you over-research, your writing style might suffer. You may find yourself spending too much time discussing minutiae rather than putting forth actionable prose for your reader. With either problem, you will lose your audience. Stay away from these pitfalls by remembering that less is more when researching your work.

The Pitfalls of a Poorly Researched Story

When you don’t take time to properly research your story, it has a tendency to read like fiction. Readers will catch on if they can spot inaccuracies in your characters or setting. They might not be sure exactly what is off, but they’ll notice that something isn’t right. Experts in certain fields won’t be too excited with inaccurate depictions of their daily lives. As fiction writers, we give from our imaginations, but those imaginations must be fed useful facts in order to properly function. A poorly researched story can come across as nothing more than nonsense without the proper underlying facts. Every good lie is based in truth. If there are no truths woven into your fictional world, then everything falls apart and becomes just that: fiction. Not just bad writing but writing that could seriously harm your professional reputation as an author.

If you’ve put little effort into researching a topic, readers may start to wonder why any other aspect of your story deserves attention and consideration. If you go so far as to deliberately hide inconsistencies and mistakes for fear of ruining an otherwise engaging narrative or misleading readers about actual conditions…well, good luck convincing anyone of anything else again. Write at all costs? Not so much…not if that cost is one’s integrity as an artist and human being committed to telling honestly rendered stories informed by some semblance of reality.

-R.E.

-

10 Great Books We Love About Writing

What makes the perfect book about writing? It should be engaging, relevant, and fun to read. It should be packed with tips that are easy to digest, even if you’re not an experienced writer yourself. It should also have the same effect on your writing that you’d get from joining a great writer’s group or working with an editor or coach—it should inspire you to keep improving your craft so that your writing reaches its full potential.

When you aren’t reading for research or for fun or to give someone your opinion on their manuscript, you should read to be a better writer. You’re editor can’t do all the work. We’ve put together a list of 10 books written with making you a better writer in mind. With these 10 books on your shelf (you should read them first, of course) you’ll be armed with a wealth of knowledge and inspiration as you embark on your writing quest.

Read the list. Then read the books. Then get back to writing because we won’t be held responsible for a dip in your daily word count.

-R.E.

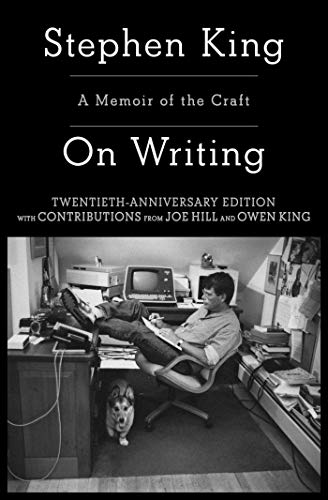

On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft

– Stephen King

Candid advice is going to come from a lot of people once you announce your intentions to write.

Choosing which advice to follow can be tricky. A literal tome of GOOD advice can be found in Stephen King’s On Writing which gives a look into the process that serves one of the worlds most recognizable writers. This book offers advice that will not only help you to be a better writer, but to feel more like a writer and for a new writer, that can be a large part of the struggle. This advice serves writers who have been at their craft for a while as well. Many veteran writers note their appreciation for the words and sentiments that King lays out with a conversational and personal approach.

In his book, King discusses many of his struggles with writing and how he eventually came to define what it meant to be a writer. In short, It’s not about making money, getting famous, getting dates. It’s about staying awake, he writes. The scariest moment is always just before you start… jump out of your airplane and pull your ripcord. Your instincts will take over from there. This might be exactly what some people need to hear in order to know they’re on their way—just like King was. We all have our own stories about doubt, obstacles and worries; they’re part of what makes us human beings.

Though we may never put them into words as eloquently as Stephen King has done so in On Writing, perhaps his most valuable point lies within his title: by understanding what writers do or who writers are isn’t important at all—it’s knowing how writers feel that really counts.

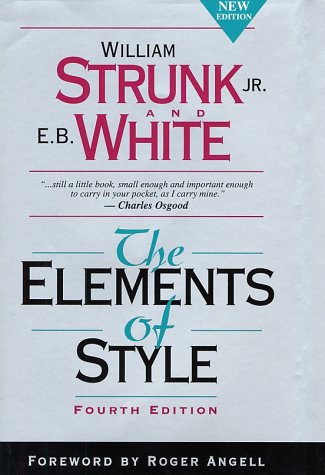

The Elements of Style

– William Strunk Jr. and E.B. White

Rules are rules. Whether you choose to break them or follow them, it is imperative that you first know them. No one, I think, is more apt to divulge these rules to you than the zealot William Strunk Jr. and his most enthusiastic study E. B. White. This classic book is an editor’s best friend. It covers all areas of writing, including grammar, punctuation and word usage. It also offers advice on how to write clearly and concisely.

The duo share their passion for words in a way only seasoned writers can. It’s hard not to fall in love with literature after reading The Elements of Style. You can find it in many different versions—everything from a pocket-sized reference guide to full-length editions with plenty of examples—so you can pick one that fits your needs. If you don’t already own a copy, consider buying one today.

This book is for everyone, but I particularly recommend it to new writers. It’s a short and sweet book of advice and rules of thumb for better writing. You can read it in an hour or two and learn a ton. The advice still holds up 80 years after its original publication date. All great writers own a copy of Elements on their shelf, and I think every writer should too.

The Book of Forms

– Lewis Turco

When you first pick up a pen, it’s natural to wonder how your creations stack up against those of seasoned authors. If you’ve ever had trouble finding your style and voice on paper, Lewis Turco’s The Book of Forms will help. It contains six forms — sonnet, haiku, limerick, ballad, pantoum and ghazal — which each feature different rhyme schemes and stanza patterns. By working through each example in order (the book starts with some basic tips on structure), you’ll be able to write some great poems that suit your personal style. After all, no one knows your writing better than you do!

If you want to know how to write poetry, start with studying poetic forms. You can’t just wing it when it comes to crafting great verse—you need something more than inspiration. This book covers prosody—that is, writing in meters and rhyme schemes—as well as all of the most common poetic forms used in English. That’s useful no matter what genre or medium you’re working in. It will give you not only an understanding of how poems are put together but also some practice putting them together yourself. Not sure where to begin? Try building a sonnet or two with these tips on getting started writing poetry.

Zen in the Art of Writing

– Ray Bradbury

While many of us may know Bradbury as a science fiction writer, his nonfiction collection of short essays about writing is inspiring. Whether you’re just beginning to write or have been writing for years, Zen in the Art of Writing will leave you with a renewed sense of excitement and purpose. The amount of knowledge it holds is immense – from great storytelling tips to observations on what it means to be a writer – and once you start reading, it becomes almost impossible to put down. The author focuses primarily on giving helpful tips for writers, such as his Rule No. 12: Don’t cramp your style. Some of

Bradbury’s more unusual writing advice includes: Use your imagination as a tool, not as an escape from reality and Fear and fatigue can’t exist in you if you keep yourself open and alert and flowing with new information. It’s no surprise that Zen in the Art of Writing is considered one of those must-have books for aspiring novelists. Whether or not you’re planning to become a famous writer, it has inspired countless people over decades. Perhaps it will inspire you too!

This book is an interesting mashup of memoir and writing advice. He remembers what it was like to be a young writer, lost in inspiration, but he also gives keen advice about how to write well. While parts are out of date—and I have to admit that when Bradbury says to keep our adverbs dear I cringe just a little bit—the heart of his advice is still incredibly solid. The goal, Bradbury reminds us throughout Zen in the Art of Writing , is to find your voice and express yourself honestly. A great book for both aspiring writers and established ones who can get stuck in a rut or simply feel unhappy with their work.

Save the Cat: The Last Book on Screenwriting You’ll Ever Need

– Blake Snyder

This book is a practical manual to story structure and character creation. It’s a must read for any aspiring screenwriter, but you’ll get just as much out of it if you’re writing novels or short stories. Blake Snyder breaks down your screenplay into fifteen different beats and then provides exercises that help you nail each beat. For anyone interested in how to turn an idea into a well-structured, three-act narrative, Save The Cat! should definitely be your reading list.

Blake Snyder’s Save The Cat! is a great book that shows writers how to do something that seems deceptively simple: start their screenplay with a compelling character whose goal is clear. It teaches how to create better stories by following some simple rules, one of which is writing about what you love. You’ll learn everything from A-stories and B-stories, inciting incidents, heroes and heroines, reversals and payoffs, The Bad Guy Always Gets His—and how they apply to scripts for just about any genre out there. Whether you want to write your first feature film or just want some tips on improving your own work, you can definitely benefit from reading Save The Cat!.

On Writing Well: The Classic Guide to Writing Nonfiction

– William Zinsser

The key to writing well is simple: write a lot and read a lot. But why do so many people still think it’s about adding loads of flavor and spice, metaphors and rhetorical tricks? On Writing Well lays out exactly what to do, why you should do it, and how to do it well. The good news is that good writing isn’t rocket science; it’s much simpler than that. Zinsser presents 10 basic principles for crafting clear, concise prose without sacrificing interesting details or important nuances. Economy means saying more with less—it does not mean uninteresting or vague or uninformative. The only way to be understood is to be yourself—and who else would you rather be than yourself? This book will show you how!

A best-seller on writing nonfiction since 1976, Zinsser’s guide gives a solid introduction to several aspects of professional writing, including argumentation and storytelling. His advice is pertinent for any level of experience. If you need help with practical advice on how to craft a story or build a strong essay structure, get your hands on a copy immediately. Highly recommended for anyone who writes nonfiction professionally.

Bird by Bird: Some Instructions on Writing and Life

– Anne Lamott

In her signature style, Anne Lamott uses Bird by Bird to talk about life, creativity and writing. It is witty, fun and filled with practical advice. This book should be read by anyone who’s ever felt frustrated at their inability to get a story on paper or anyone who struggles with self-doubt when it comes to expressing themselves through writing. How do you find a style? How do you deal with bad reviews? How do you develop courage in your daily life so that you have it when it comes to writing? All these questions are answered in an easygoing but thoughtful manner.

This book is about much more than writing; it’s about life too. If you enjoy her writing (and if you don’t, I can’t help you), then try her novels; she has several great ones that are all semi-autobiographical in nature and always interesting. This particular book is useful to writers at any stage in their career because it provides sound advice on how to get over writer’s block, not take yourself too seriously, and really do your best work when you need to most.

Whether you are a budding author or have been in love with words for years, you will fall in love with Lamott’s work after reading Bird by Bird. With her signature candor and humor, she describes how writing can be personal and can become an extension of who we are and what we believe in. She often takes herself and other writers to task while encouraging us to continue down our path to becoming great writers. This is one of those books that I re-read at least once a year, even though it has been ten years since I first read it; each time I find myself laughing out loud (probably because I share many of her foibles) while appreciating how wonderfully blunt she is about such things as balancing family life with life as an artist.

Steal Like an Artist: 10 Things Nobody Told You About Being Creative

– Austin Kleon

If you’ve always wanted to be a writer but you’re not sure how to go about doing it, Steal Like an Artist is an inspirational guide for artists, writers, musicians and anyone who wants to add creativity to their life. This book encourages artists and makers of all kinds to embrace their influences and make something original from them by adding their own voice, spin and style. It’s a great reminder that we’re all standing on shoulders of giants: without artists who came before us we’d never have known just how incredible art can be. If you’re looking for some motivation or inspiration then Steal Like an Artist is a must-read.

If you want to create something original, your first step is to familiarize yourself with everything else out there. With insights from those who created some of America’s most popular culture, Kleon offers that all creative work builds on what came before. This book shows readers how to approach their work as an artist would, breaking down such skills as observation, persistence, originality and process into concrete, easy-to-implement tactics that will improve your output. Kleon gives good practical tips on finding ideas and inspiration – both his own process of capturing interesting things he sees and hears and examples from other artists – but also writes beautifully about why we do what we do: All creative work is done in service of something greater than itself. When you’re making something new it’s always because there’s something out there that needs to be expressed.

Wonderbook: The Illustrated Guide to Creating Imaginative Fiction

– Jeff VanderMeer

Some call it magic. We just call it what works. From best-selling author Jeff VanderMeer comes a spectacularly beautiful guide that shows you how to conjure up wondrous stories, characters, and worlds—and captivate your readers for years to come. Through jaw-dropping illustrations, VanderMeer reveals some of fiction’s most closely guarded secrets. He answers questions like: What are quiet scenes? How can I make my narrator funny? Why do I need an inciting incident? Explore these answers—and more—in Wonderbook. Packed with practical tips on writing science fiction, fantasy, thrillers, crime novels—even poetry! Here’s everything you need to know about crafting stories that grab editors’ attention (and get published!). Writing is an art form; let Wonderbook be your muse.

VanderMeer discusses a number of techniques for creating vibrant imagery and characters, as well as his take on worldbuilding, inspiration, and other general writing wisdom. VanderMeer doesn’t hold back in criticizing popular tropes or naming names—the curse of ‘fantasy’ he calls it—and he does so with a self-effacing sense of humor that makes it easy to hear him out. Wonderbook is accessible yet challenging, witty yet sobering, and I’ve probably marked up my copy more than any other book I own (except for maybe Dracula). This is one of those books every writer needs to read at least once: insightful and inspirational even when you disagree with VanderMeer’s criticisms or advice.

Writing Down the Bones: Freeing the Writer Within

– Natalie Goldberg

Having recently picked up my copy of Writing Down The Bones again, I can say it’s still one of my all-time favorites. It’s so good I even read it during lunch breaks at work! This book provides excellent advice for how to get started writing and keep that motivation going. Natalie writes clearly and enthusiastically about how you don’t need an MFA or anything fancy to write; just get out there and start putting words on paper, wherever you are. She teaches you how you can write by simply sitting down and doing it.

This is a great book for understanding that writing doesn’t have to be perfect, just let your thoughts flow through your fingertips onto paper. This is definitely one of my favorite books on writing because I don’t believe you have to have a degree or special training in order to be a writer, anyone can do it if they practice everyday. I still use The Freewriting Exercise when I get stuck when trying to figure out how to start my articles, letters, emails etc… The way she breaks down what many consider complex techniques into simple easy steps that anyone can accomplish are exactly what people need in order to get started with writing every day.

The whole attitude of anything worth doing is worth doing badly in your spare time until you can do it better later is something I want to emulate. A great first book for anyone interested in improving their writing skills. Writing Down The Bones is an essential read if you’re serious about freeing your own creativity.

-R.E.